“Lawyers Guns and Money” by Warren Zevon retrieved from http://images.45cat.com on December 17, 2014.

Today we’re going to talk about lawyers, guns and money. But, not the hit song.

In our previous posts in the Justified series:

- JUSTIFIED: Does Pennsylvania Law Allow for Use of Force in Self-Defense?

- JUSTIFIED 2: Defense of Others

- Justified Part 3: The Castle Doctrine and Stand Your Ground

we discussed when the law protects those who use force, particularly deadly force, in self-defense. While those posts focused on the laws which protect a justified shooter from criminal penalties, this post will examine whether the law protects a justified shooter from civil liability.

Those who face criminal penalties stand to lose their freedom. Those who face civil liability stand to lose their money. Many people don’t realize that these two systems are completely different. In general, even if criminal charges fail at trial, are dropped before trial, or are never even brought, that does not preclude you from civil liability. Why? Because criminal courts and civil courts demand two substantially different burdens of proof.

In order to be found guilty in the criminal courts, the government must prove every single element beyond a reasonable doubt. The finder of fact (usually a jury) must find that no reasonable person could conclude any other way. This is a very high threshold, and is difficult to meet.

However, a plaintiff in a civil lawsuit only has the burden to prove his claim typically “by a preponderance of the evidence,” which means more likely than not. Even if reasonable minds might differ, a plaintiff can still succeed.

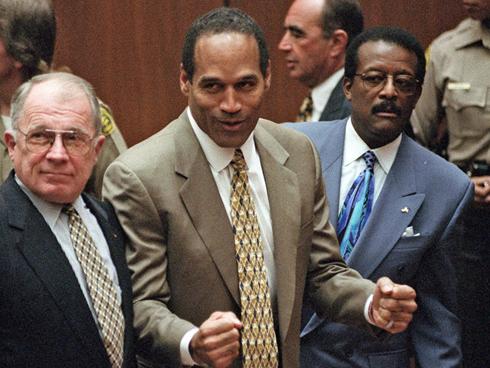

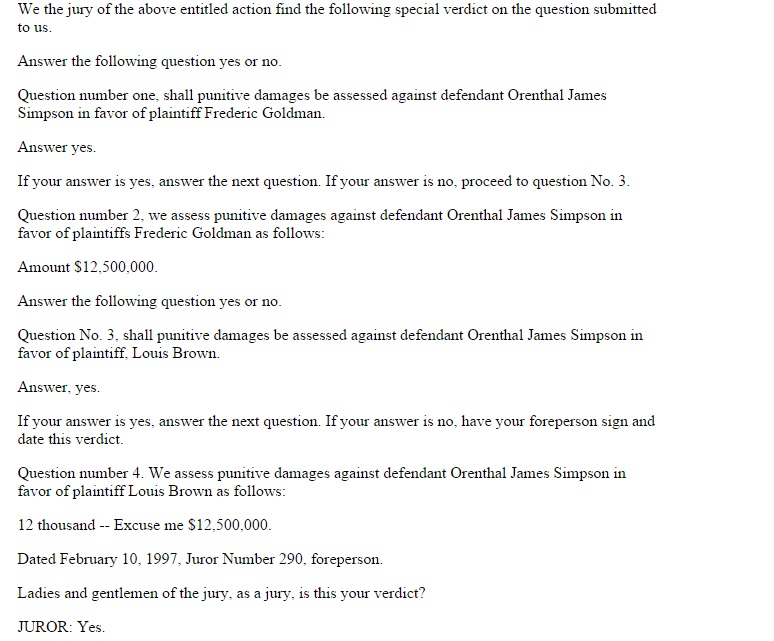

Perhaps one of the greatest historical examples of how the standards differ lies in the highly publicized O.J. Simpson cases. Simpson was charged with the murder of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman. In that case, People of the State of California vs. Orenthal James Simpson, Simpson was ultimately acquitted. In the criminal case, in returning a verdict of not guilty the jury essentially found that the prosecutor had not proven Simpson’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. However, following the acquittal, Brown and Goldman’s family members brought a civil suit against Simpson for the deaths. This time, abiding by the lesser “preponderance of the evidence” standard, the jury found Simpson liable, awarding the plaintiffs a total of $33.5 million between compensatory and punitive damages. However, the civil jury’s finding of liability only represents a determination that it is more likely than not, even if only 50.01% likely, that Simpson was in fact the killer.

O.J. Simpson celebrates “Not Guilty” verdict following criminal trial. Photo retrieved from usatoday.com on December 17, 2014.

O.J. Simpson civil trial verdict transcript. Retrieved from http://simpson.walraven.org/feb10-97.html on December 17, 2014.

As discussed in our initial post in the Justified series, [JUSTIFIED: Does Pennsylvania Law Allow for Use of Force in Self-Defense?] justification is an affirmative defense. If the prosecutor fails to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused is not entitled to protection under a justification defense, the accused is not guilty. How does that come into play in a civil suit? Can the perpetrator’s survivors still nail the accused in civil court?

In Pennsylvania, the answer is no. A civil immunity statute protects those who are justified in using force: “An actor who uses force . . . in self-protection as provided in 18 Pa.C.S. § 505 . . . is justified in using such force and shall be immune from civil liability for personal injuries sustained by a perpetrator which were caused by the acts or omissions of the actor as a result of the use of force.” 42 Pa.C.S.A. § 8340.2. In essence, if a shooter is truly justified under §505, he is protected from civil liability. This statute allows the judge to throw out a civil suit for a justified shooting as a matter of law before it even gets to trial. While matters of fact may be decided by a jury, matters of law are reserved for the judge.

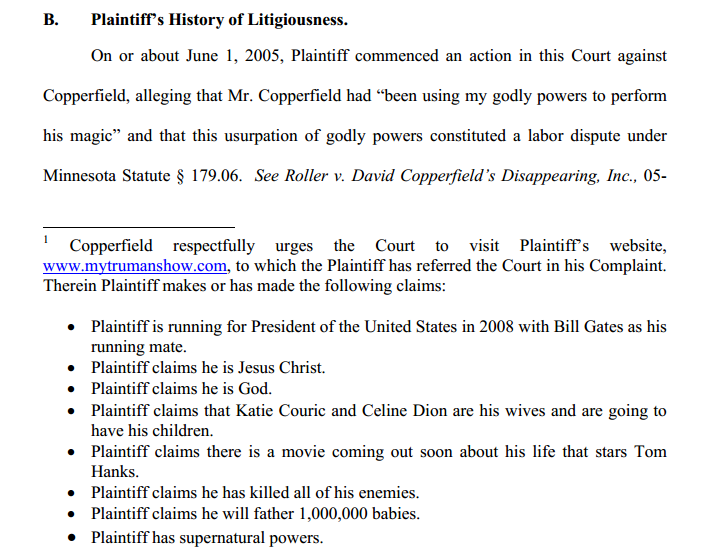

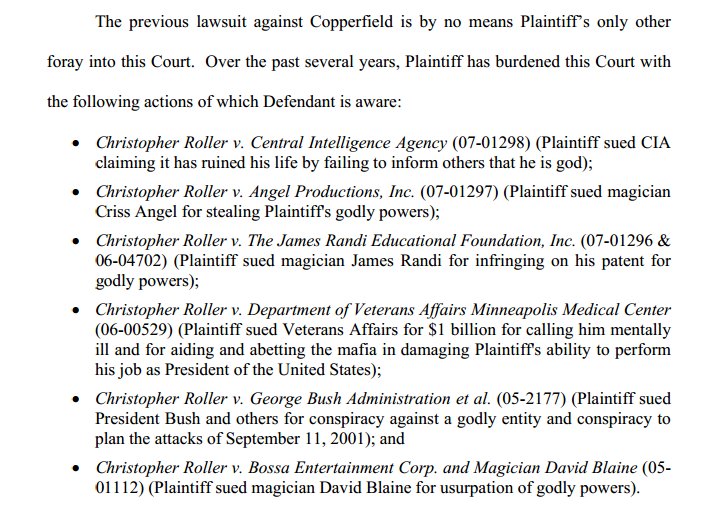

Does that mean if somebody is justified in using deadly force, he can’t be sued? Unfortunately, that isn’t what it means. A plaintiff can initiate a lawsuit for anything, regardless of whether the lawsuit states a legitimate cause of action (there’s actually a nutjob out there who sues magicians regularly alleging that these magicians have stolen his “godly powers”). At the initiation of a lawsuit, the complaint is officially filed with the clerk. The clerk doesn’t have the ability to review the merits of the case. Consequently, as long as the plaintiff has the necessary papers and the filing fee, the lawsuit will be filed.

Excerpts from Motion to Dismiss filed by Defendant (Copperfield) in Roller vs. David Copperfield’s Disappearing, Inc.

Excerpts from Motion to Dismiss filed by Defendant (Copperfield) in Roller vs. David Copperfield’s Disappearing, Inc.

If you’re served with a lawsuit, it’s important to see an attorney immediately.

Just because a lawsuit is ridiculous, or even frivolous, doesn’t mean you can just throw it in the garbage.

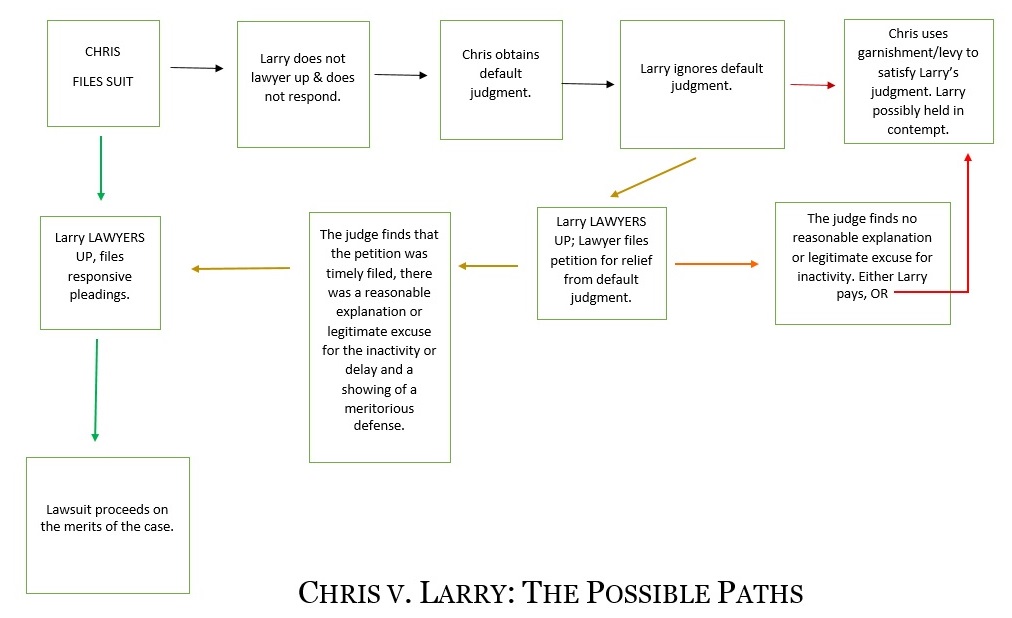

Much like medical issues, the sooner you “catch” a legal problem, the better chance you’ll have of dealing with it effectively. When served, you only have a limited time ―20 days― to file your responsive pleading. Failure to do so gives the plaintiff the opportunity to obtain a default judgment. Once the 20 day period has elapsed, the prothonotary can upon request enter default judgment on behalf of the plaintiff so long as the plaintiff provided the defendant with at least 10 days notice of their intent to file default judgment. Even though the prothonotary will not review the merits of the case, a default judgment is valid and binding just like any other judgment.

A judgment isn’t just a piece of paper either. If the defendant doesn’t pay in accordance with the order, several bad things can happen. First, the defendant can be held in contempt of court for failing to comply with a court order. The plaintiff will also have other alternatives to collect on the judgment, such as garnishment and levy. Perhaps the least of all, yet still unfavorable, an unsatisfied judgment also has a serious negative impact on a defendant’s credit score.

In some situations, it is not too late for the defendant, even if default judgment is entered. A defendant can petition to have the default judgment set aside. For a judge to grant this application, there must be reasonable explanation or legitimate excuse for the inactivity or delay. Defective service can be a reasonable explanation or legitimate excuse worthy of opening a default judgment. For example, if the plaintiff served the wrong guy, and the real defendant had no idea that the lawsuit existed, a judge would not be inclined to let the default judgment stand. On the contrary, “the lawsuit was nonsense, so I crumbled it up and threw it in the garbage” is neither a reasonable explanation nor a legitimate excuse.

In some situations, it is not too late for the defendant, even if default judgment is entered. A defendant can petition to have the default judgment set aside. For a judge to grant this application, there must be reasonable explanation or legitimate excuse for the inactivity or delay. Defective service can be a reasonable explanation or legitimate excuse worthy of opening a default judgment. For example, if the plaintiff served the wrong guy, and the real defendant had no idea that the lawsuit existed, a judge would not be inclined to let the default judgment stand. On the contrary, “the lawsuit was nonsense, so I crumbled it up and threw it in the garbage” is neither a reasonable explanation nor a legitimate excuse.

What happens if your attorney is able to make the default judgment go away? Well, it’s back to square one. Responsive pleadings still must be filed. It is only now that a judge will review the merits of the case.

Let’s look at this using a hypothetical featuring our PennLAGO characters, Larry the LAGO and Chris the Criminal. Suppose Larry shoots Chris, and is justified under §505. Legally, Larry will be protected from civil liability. However, this might not prevent Chris (if he survived the shooting) or Chris’s survivors from bringing a lawsuit. Remember, anybody can sue anybody for anything. If and when suit is filed, and Larry is served, Larry must choose how to proceed. The flow chart below provides some brief and general examples as to how the different approaches are likely to pan out.

As you can see, Larry fares best if he deals with the lawsuit immediately. While it’s unfortunate that Larry has to deal with the bogus lawsuit to begin with, he will save himself a lot of trouble by attacking it directly rather than sweeping it under the rug.

As you can see, Larry fares best if he deals with the lawsuit immediately. While it’s unfortunate that Larry has to deal with the bogus lawsuit to begin with, he will save himself a lot of trouble by attacking it directly rather than sweeping it under the rug.

Recall our discussion about justification as an affirmative defense in the criminal arena. The statute relieving civil liability also serves as an affirmative defense. This means that it must be raised in order for the protections to apply. Even more importantly, in a civil suit, if an affirmative defense is not raised, it is waived. In Pennsylvania, the procedures for raising an affirmative defense in a civil suit are extremely specific (for starters, affirmative defenses must be pleaded in a separate section of a responsive pleading with a heading reading “New Matter”).

To ensure that compliance is met, and any affirmative defenses are preserved, it is vital to seek counsel. Procedural errors can be costly, and it is nearly impossible to navigate through the rules of civil procedure solely based on life experience and intuition. Civil procedure is neither exciting nor appealing (even to most lawyers), and as a result, doesn’t make for good entertainment or dinner conversation. Almost everybody has learned a shred of law from the news, television, or personal experience. It’s likely that not a shred of that shred has to do with civil procedure. These rules are anything but common knowledge. Expecting to know them would be like expecting somebody who’s never seen a baseball game to know the infield fly rule.

Let’s look at it another way. Would you walk into a casino, head over to a roulette table, and put your entire life savings on black? If not, then it would be wise to employ counsel to handle your civil litigation. While facing the litigation without an attorney might not entirely be a game of chance, it is certainly a gamble. And there’s not a chance on Earth that you’ll leave the courtroom doubling your money on that gamble.

Now it may seem unfair that degenerates like Chris the Criminal can file lawsuits with no basis against good faith players like Larry the LAGO. It certainly is, and the legislature has recognized this. The civil immunity statute also includes a fee shifting provision. If a justified shooter “prevails in a civil action initiated by or on behalf of a perpetrator against the actor, the court shall award reasonable expenses [including attorney fees, expert witness fees, court costs and compensation for loss of income] to the [justified shooter].” 42 Pa.C.S. § 8340.2(b). In other words, if Chris or his survivors do file a lawsuit against Larry with regards to a justified shooting, and Larry wins, Chris or the survivors would have to foot the bill.

Practically speaking, it’s important to keep in mind that this fee shifting provision doesn’t come into play until the litigation is over. That means that the necessary funds —at minimum, the attorney fees, any expert witness fees and court costs— will come out of the defendant’s pocket unless and until he receives a judgment in his favor. If he settles just to move on with his life, he gets nothing. Even at this point, the court will determine a reasonable amount for these costs, and will award the defendant that amount. This amount may or may not be as much as the defendant actually spent. Once the judge awards fees, the defendant must try to collect from the plaintiff. As you would imagine, plaintiffs like Chris the Criminal often don’t have any money or assets to satisfy the judgment. So there are a few instances in which a successful defendant could potentially walk away short.

A defendant who endures the hassle of a lawsuit holding no basis might also have a claim under 42 Pa.C.S.§ 8351 for wrongful use of civil proceedings. The statute provides a cause of action against those who participate “in the procurement, initiation or continuation of civil proceedings against another” and

- act in a grossly negligent manner or without probable cause AND

- the action was filed for an improper purpose, AND

- the proceedings have been terminated in favor of the original defendant.

Because the act only requires participation, an attorney who brings the initial bogus claim can end up on the hook for doing so. Like the fee shifting provision of §8340.2, the initial action must be complete with no opportunity remaining for the original plaintiff to prevail. Unlike the fee shifting provision, a claim for wrongful use of civil proceedings is brought in an entirely separate lawsuit, so bringing this separate cause of action can be very time consuming. Lastly, the statute clearly states, and case law confirms, that the original action must have been filed for an improper purpose. This will not always be the case. Just because a lawsuit has virtually no chance to win, doesn’t necessarily mean it was filed for an improper purpose. Sometimes, it is the case. For example, let’s suppose Larry uses justified deadly force against Chris, and Chris doesn’t survive. Chris’ cousin Corky, knowing of the civil immunity statute, files a lawsuit on Chris’ behalf anyway. He figures it will cost Larry at least $10,000 to defend the lawsuit. His plan is to offer to settle immediately for $5,000, hoping that Larry will just pay the $5,000 in the interest of efficiency. In this instance, if Larry refuses to settle, wins, and can show Corky’s actions meet prongs one and two of § 8351, he will have a separate cause of action. Remember, in this separate civil action Larry will only have to prove his claim by a preponderance of the evidence, meaning “more likely than not.”

Because the act only requires participation, an attorney who brings the initial bogus claim can end up on the hook for doing so. Like the fee shifting provision of §8340.2, the initial action must be complete with no opportunity remaining for the original plaintiff to prevail. Unlike the fee shifting provision, a claim for wrongful use of civil proceedings is brought in an entirely separate lawsuit, so bringing this separate cause of action can be very time consuming. Lastly, the statute clearly states, and case law confirms, that the original action must have been filed for an improper purpose. This will not always be the case. Just because a lawsuit has virtually no chance to win, doesn’t necessarily mean it was filed for an improper purpose. Sometimes, it is the case. For example, let’s suppose Larry uses justified deadly force against Chris, and Chris doesn’t survive. Chris’ cousin Corky, knowing of the civil immunity statute, files a lawsuit on Chris’ behalf anyway. He figures it will cost Larry at least $10,000 to defend the lawsuit. His plan is to offer to settle immediately for $5,000, hoping that Larry will just pay the $5,000 in the interest of efficiency. In this instance, if Larry refuses to settle, wins, and can show Corky’s actions meet prongs one and two of § 8351, he will have a separate cause of action. Remember, in this separate civil action Larry will only have to prove his claim by a preponderance of the evidence, meaning “more likely than not.”

It’s important to understand the civil implications of the justified use of deadly force. Many LAGOs are under the impression that if they use deadly force and don’t end up in jail, then the ordeal is over. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. However, to mirror the criminal protections afforded to justified shooters under §505, Pennsylvania law provides civil protections to justified shooters under 42 Pa.C.S. § 8340.2. While a civil suit may inconvenience a LAGO after a justified shooting, at the very least, the civil immunity statute provides a mechanism to prevent such a civil suit from prevailing, or even reaching a jury.